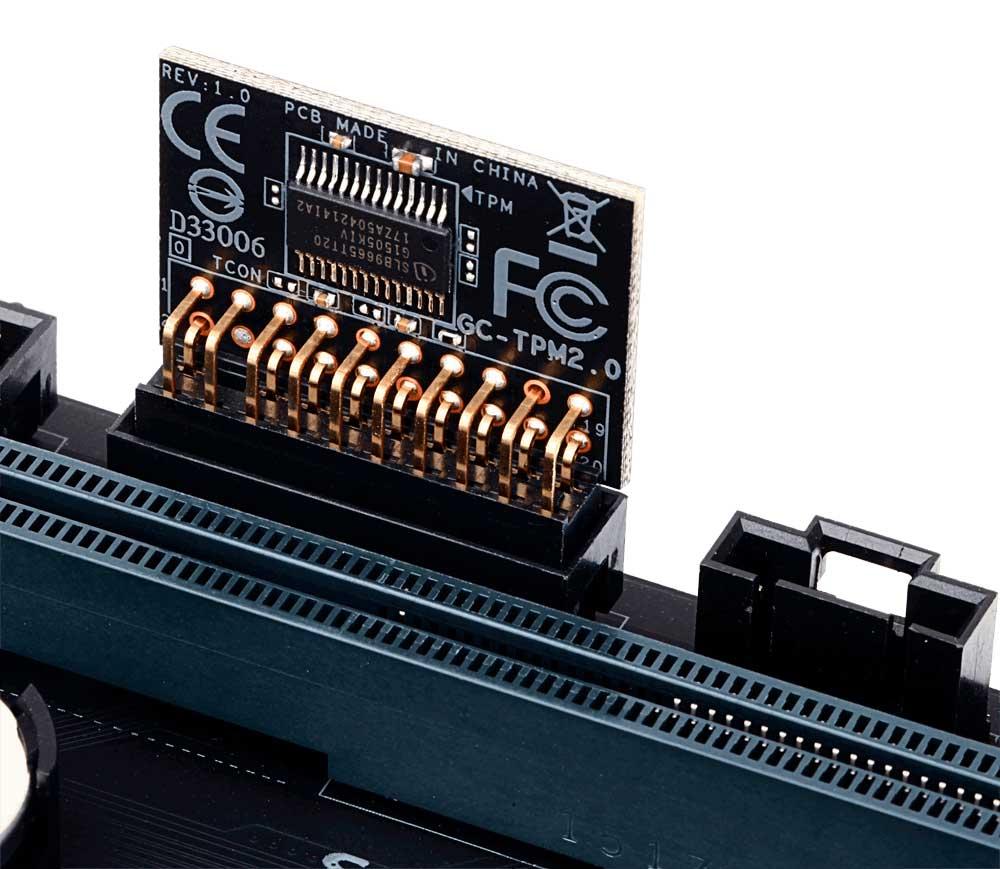

As such, it’s also the number one target for cyberattacks, with some of the world’s biggest headline-grabbing ransomware and malware attacks targeting Windows-running devices. While it has gained some competition from macOS, Linux and Chrome OS in recent years, it still dominates the global market, running on no less than 75% of all PCs currently in use. Windows is the most widely used operating system in the world. Both Windows 10 and Windows 7, however, supported TPM and used it for a variety of functions. It’s not a particularly new feature for Windows either: it was actually made a requirement for Windows 10 as well but was not enforced the way it has been for Windows 11. TPM chips have been around for a while but have only been widely used in IT-managed business laptops and desktops. According to David Weston, Microsoft’s Director of Enterprise and OS Security, it helps protect encryption keys, user credentials, and other sensitive data behind a hardware barrier so that malware and attackers can’t access or tamper with that data. A TPM chip is a chip that conforms to that standard and can either be integrated into a computer’s motherboard or can be added separately into the CPU. TPM, also known as ISO/IEC 11889-1, is an international standard for secure cryptoprocessors, dedicated microcontrollers designed to secure hardware through integrated cryptographic keys. The company’s overall aim is to create chip-to-cloud Zero Trust out of the box. The move is part of Microsoft’s broader push for security by design, a concept that is central to several data protection laws, such as the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

TPM 2.0 is required to run Windows 11 as an important building block for security-related features. Microsoft unveiled Windows 11 this summer and, when system requirements for the update were later released, one, in particular, drew considerable attention: the Trusted Platform Module (TPM) version 2.0.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)